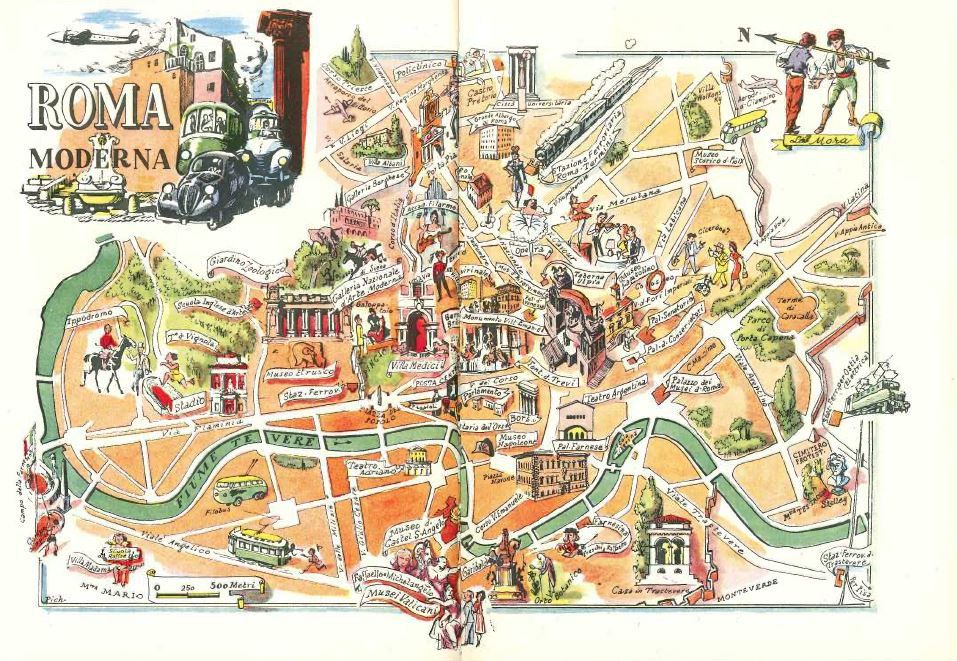

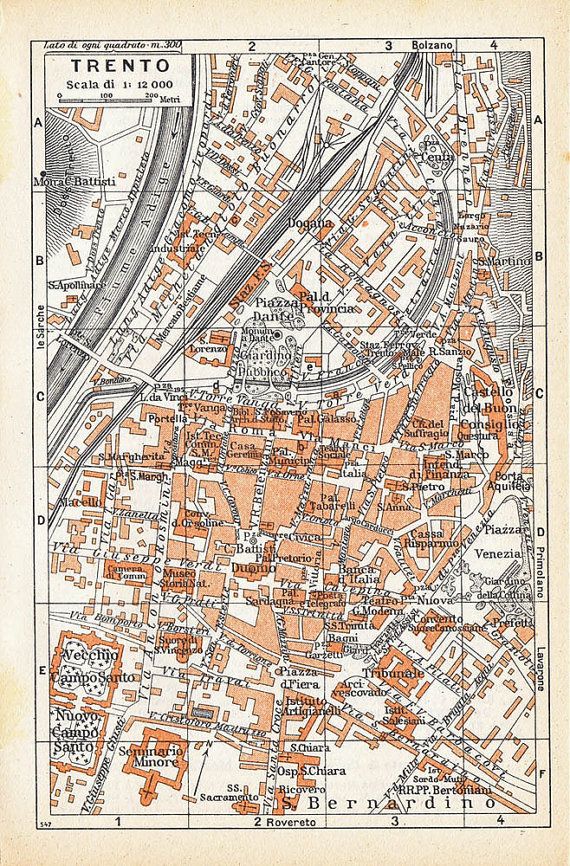

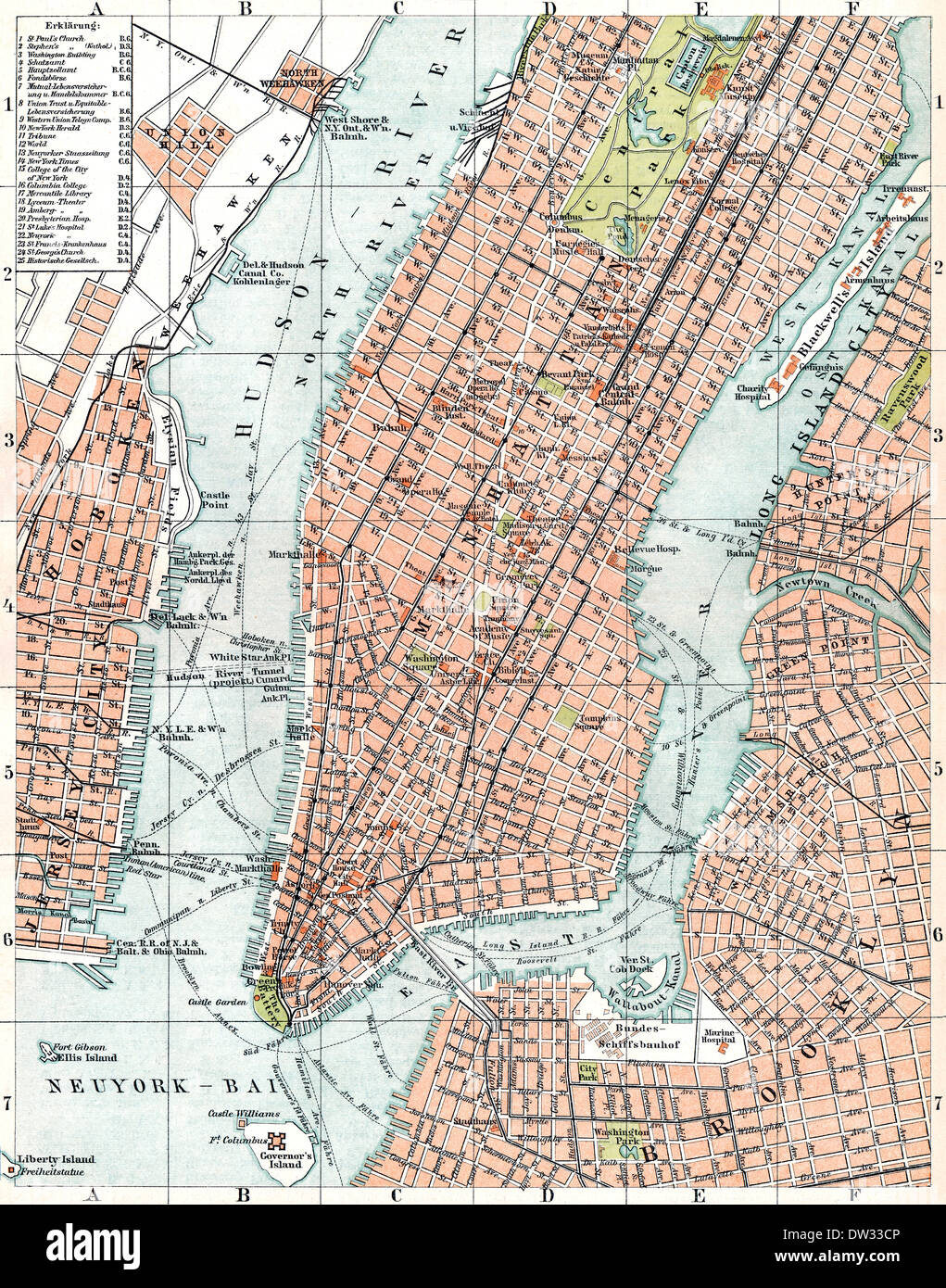

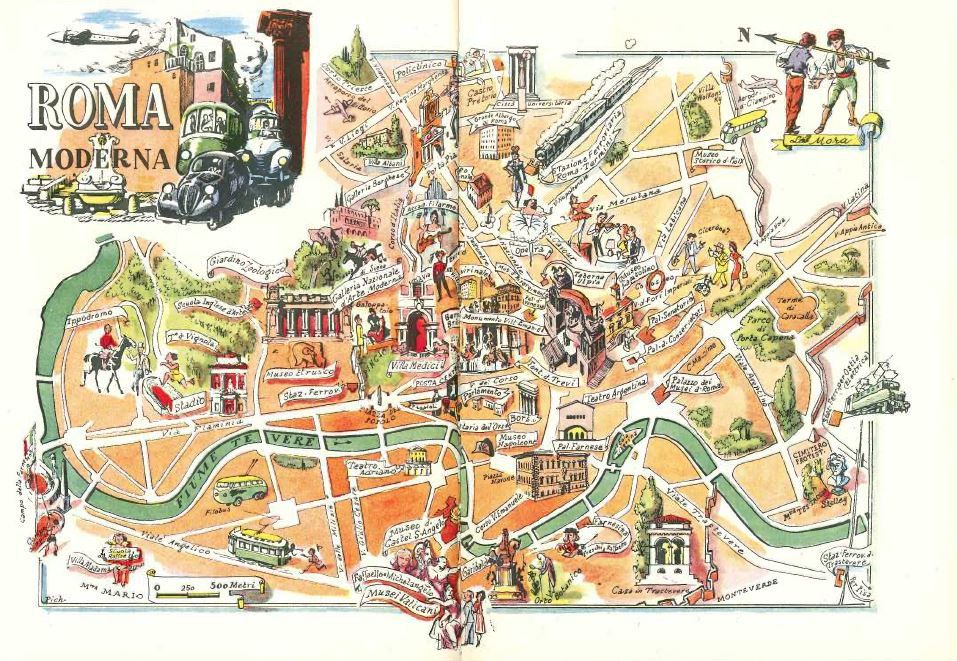

Illustrated city maps include some of my favorite 1950s-style cartography.

Illustrated city maps include some of my favorite 1950s-style cartography.

The Mullingar Lea / The Flogging Reel

Originally written in 2018.

Oliver and I are in a valley in Gitega Province, Burundi, surrounded by fields. We're walking to visit some fish ponds we were told about. Valleys here have completely flat bottoms. The streams have been re-routed into channels, and an intricate series of dams funnels water into different canals that feed the fields.

A man shows us his fish pond. It's the middle of three, and his is perhaps the largest one. He is carefully adjusting the inflow with a plastic bottle fashioned into a sieve. I attempt to ask how big the fish are. He nods.

We pass a Hadada Ibis feeding, its long curved beak poking into the mud along a canal. Its piercing squawk fills the valley, but it continues feeding, absentmindedly talking to itself in shouts. From here, it looks like a large burlap-brown dull bird, long legs in the mud, long beak in the mud, feathers blending into the mud, yelling. It notices our stares and lifts off up the valley, showing off its brilliant green shoulders in the sunset. As it lands far in the top of the valley, we hear its protestations as clear as ever.

There are no large predators in Burundi, and perhaps no large wild mammals at all. We are told they were all shot in the last war. In their palpable absence, birds thrive.

An African Pied Wagtail sits in the path in front of us. These birds don't say much, but quietly hop along the ground in constant motion. They look like cartoon prisoners, in white and black stripes. Perhaps their constant wiggling is because they are always about to make a dash for it.

We head back across the hospital, towards the housing complex where we've been given an apartment for our stay. Large trees surround the houses, pines, locusts, eucalyptus, broadleaves, miombos. Caleb says the pines were introduced by the Belgians. The higher slopes of these wooded mountains are densely colonized. The sighing of the wind through their branches reminds me of the Ponderosas back home.

The trees near our apartment are filled with birds, making their presence known loudly. Each has an incredible song. There's a deep "dee-dwoip" which wakes us early, as if someone is blowing into a jug outside our window. A shrill "ke-ke-ke-ke-ke-ke" never ends during the day, its owner the smallest and dullest chatterbox. The tangle of voices changes and morphs after sunset, speaking less often but with more mystery. Most of the birds you see are silent, while the birds you hear are invisible.

Gerard shows us pictures of owl chicks he's found, recently fallen from their nest. One has died, but the other hisses at him from under a bush. The mother watches from a tree nearby.

The dirt here is a deep orange-red clay. Most everything is cultivated, but the margins grow short grasses that poke up between various basalts. I have been warned of bugs that crawl under your toenails, but everyone here, including myself, wears flip-flops. The soil smells sweet.

We don't see many pets here, dogs or cats. Napoleon has a dog, Simba, a tawny bitch with pointy ears. She looks like a cattle dog from back home. Friendly and quiet, she smells our weird western behinds with curiosity. Many of Napoleon's neighbors have pigs in their yards, with tall woven fences that are green and lush.

On our way to dinner, we see two hawks fighting over a carcass stuck in a tree fork high above. One hawk is eagerly ripping its meal, shaking the tree branch in his haste to gorge. The other hawk looks on, loudly complaining, while the carcass gives faint whimpers less and less frequently. Perhaps this is the end of the other owl chick.

Pied crows are everywhere, the insufferable pranksters of every gutter, tree, and trash pile. One in particular has earned notoriety for swallowing a pill bottle which has now grown out of its neck. Nobody knows how it's survived, but the bottle has been protruding haphazardly for over five years now, earning one crow instant fame and recognition by the humans.

In Bujumbura, two tame Grey Crowned Cranes stare blankly at flowers, picking daintily across a low wall on gangly legs. They stare out over Lake Tanganyika, their top-knots outlined against the bright fog. After a few turns on the wall, the taller bird gets bored and hops down to pirouette in the grass until suddenly sprinting across the lawn. It appears that the cranes take "living in the moment" quite seriously, aimlessly carousing without a care.

Later, in Uganda, we are visited by Marabou Storks while drinking coffee on the shore of Lake Victoria. The storks are silent, but their huge wings beat a drumroll announcing their arrival. These are the storks who went to seed, spending a little too much time in the sun, or perhaps had disastrous careers as pyrotechnicians. They seem to smile at their own joke, waiting for someone to catch the drift. After waiting in vain for me to chuckle, they swoop up into a tree to drop gifts on unsuspecting walkers.

On our way back from the village one night, Oliver fills me in on an english teacher's experience. While staying in a hut in Africa years ago, he was visited by strange sounds and voices. A skeptic, he investigated but could find no cause. The screams and shouts tormented him. I search Oliver's tone to find any hint of sarcasm. It's too dark to see if he's smirking, but I am not easily unsettled. Our conversation is abruptly interrupted by an incredible screeching howl from up ahead. It sounds vaguely like a child yelling or a woman screaming a long way off. My heart leaps up.

A few steps further, and we see a huge shape glide across the road. At least four feet wide, it floated in perfect silence, suspended as if weighing nothing. It floats into the trees to our left.

As we train our flashlights into the trees, we hear the screech again from our right. The flashlight darts back, to shimmer in the eyes of a moulting, screeching baby owl that sits a foot tall on the top of a wall. It hunches and yowls, annoyed by our light.

We find the mother in the tree across the road, and keep her in view as we walk past her to our apartment. She's huge, most likely a Verreaux Eagle Owl, four feet tall. She could easily knock us out. Her "ears" follow us down the road, and she hoots, pleasantly, as if to apologize for her screeching youngster.

A large brown toad crosses the road as we turn in. Perhaps he's using the opportunity to sneak past the owls, the nocturnal abazungu, and their flashlights.

I wrote this post in 2017, in Kibuye, Burundi after visiting the NICU ward at Kibuye Hope Hospital.

For decades, premature babies have been born at Kibuye Hope Hospital. Many of them haven't survived, but recent developments have started to even the odds..

These hand-made incubators were designed here at Kibuye to take advantage of cost-effective local resources. Made of eucalyptus wood, they are manufactured by a woodworker in Gitega, a city of 40,000 about an hour north of Kibuye. The incubators are equipped with a thermostat and a pair of sixty watt light bulbs. The light bulbs are mounted in a compartment underneath the incubator bed, warming the enclosed space to just the right temperature.

The NICU is a well-lit, narrow ward with tall ceilings. The beds stand in rows along one wall and single file against the other. The room is full to capacity. We follow the doctor and medical students into the space between the beds for their morning rounds.

In Kirundi, each mother in the ward is called "Mama". Each Mama watches the doctors closely, looking from face to face, as the medical team discuss the baby's progress in English. The NICU is under the supervision of a medical student and nurses during the day, with an American doctor performing rounds every morning. When the American doctor has questions, they pass through translators. "Mama, is the baby nursing well?"

A mama with a pair of premature twins sits on two beds pushed together. One baby is very small, only 1,100 grams. Mama nurses the smallest while the doctors consult. The larger twin sleeps under blankets on the second bed. A supplemental formula is prescribed.

Another baby is much larger, a three-week old admitted for jaundice. The overseeing medical student has proscribed light therapy. The teaching doctor presses the student for alternative proscriptions. Mama looks on, while gently tightening the baby's swaddle.

In any hospital, the NICU is a profound place. The freshest and most vulnerable children struggle for life, surrounded by concerned family. Healthcare workers seek solutions within narrow margins. It's a place of intense joy and loss, together.

Two days after our rounds the twins are discharged, both healthy and growing.

Aaron Schwartz's life had a strange magnetism. I was a stressed-out farm kid with no real connections, but even so it felt like there was a bright conspiracy of internet Robin Hoods, ready for you to join them. He was the internet's Little John. The Internet's Own Boy is a…

Docker for Windows uses a few Windows Containers features to provide networking to Docker containers. Sometimes (usually bad shutdowns, killing host VM, etc) those networks can be corrupted. An example error you might encounter is: Error response from daemon: HNS failed with error : The object already exists. These kinds of…

Threat modeling is a crucial activity for anybody working in software, but for somebody just starting out, it’s super intimidating. What do you search for? What’s the goal of threat modeling? Why should I care?…

My machete drips

Green foam

My boots crush pulp of

Devil’s club, fireweed,

Roses, elderberry,

Pushki spraying sap,

Salmonberries.

From below,

The new mountain path

Winds up slow.

I rest my juice-covered arms.

The sea is pinned taut.

Chest-high green

Slopes double black

To a wall of spruce.

An eagle

A tiny prick of black and white

Below us, above the bay.

Flies stick to my machete.

Stilled, I turn to again.

Here, we gather wrack

From an ancient

Tide.

Originally appeared in Hawk & Handsaw: Journal of Creative Sustainability