Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.¹

In her essay Poetry Is Not a Project², Dorothea Lasky argues that good poems can't be made from some linear intention. When a poem is forced into something like a framework or plan, it breaks something strong inside: its many-faced, kaleidoscopic uncertainty. There is power in the idea that great poems do not come from a place of statement, but from what she calls "that uncertain space, where the grand external world (meaning anything and everything) folds into the intense internal world of the individual".

The page becomes a cliff, and I am standing on the edge, feeling the impulse to jump. Writing is not so much thinking on paper as falling into a primordial caldron of self and world; my thumbnails are worn as protective hats on sea urchins feeding on my pages like seaweed.

If poetry is not a project, then what is its function? If poetry isn't for saying something, then how should it be used?

The filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky had a provocative opinion on the purpose of art, regardless of form:

The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow [their] soul, rendering it capable of turning to good.³

Art, with Tarkovsky, feels embroidered in the veil of death. Tarkovsky later compares the experience of art to a "sublime, purging trauma", in which we discover "the unfathomable depths of our own potential, and the furthest reaches of our emotions". This ploughing and harrowing uncover the "best sides of us", the treasures under the mud, and we "wish for them to be freed".

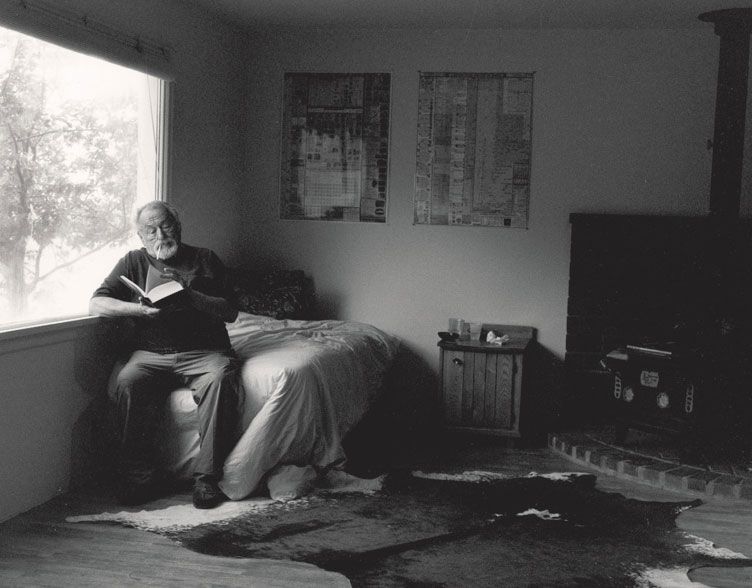

I prune myself with poems, I dig out the English Ivy that is sucking me dry, I rake up the debris covering my heart. I open a book like a toolshed, selecting the implement that suits the heart-work I am doing that day.

If poems are tools, are they only for personal experience? Do they only work on your own self?

You are just trying to strike a spark, but what fire that spark lights — is up to the person whose spark it is.⁴

With the poem's spark, a fire can be lit in each receptive reader — these fires all have different shapes, different heats. Each fire can warm a handful of good friends, throwing off its own crackling sparks. James Baldwin strongly suggested the intimacy of social change, the liberatory power of these fires:

A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven ... Societies never know it, but the war of an artist with his society is a lover’s war, and he does, at his best, what lovers do, which is to reveal the beloved to himself and, with that revelation, to make freedom real.⁵

This "great love affair"² is the harrowing and ploughing of society to discover "the best sides of us", the controlled burn of the undergrowth, and the sparking of campfires in the dark. Crucially, all of this work takes place in the heart of one reader — experiencing the trauma of a poem.

I am cradled by my enemy; we have fallen to the ground, and our hair and blood are tangled like alien blackberry vines, they bloom like algae. In his eyes I see a fate like forgiveness, like betrayal. I hang on the edge of knowing like a bristlecone.

This symphony of distress, a harmonic tension between the best sides of us and our shadow, is the bright trauma of a poem. The experience of this limbo, this "wild party"², offers a kaleidoscopic perspective. The reader is taking two paths at once, or being underwater and on shore simultaneously – torn, split, shattered, glittering between many places, times, emotions. This rent state is horrendous and exhilarating, and completely its own, indescribable outside of itself.

Poetry becomes the craft by which we explore the contradictions – the inarticulate horrors, and the wordless euphorias – of our inner selves. These landscapes have no direct parallel, and retract from description, so we paint with words like impressionists. Our own selves become lenses, black holes bending space, time, and language.

the moment is invertebrate no narrative / you’re naked with feelings you don’t / understand they bend around you like water.⁶

I will not compose poetry — but I will bring myself to myself, and not look away. I will be split apart, I will decompose, I will feel myself carried away by roots and mushrooms. I will grow fingers of leaves, and fruit into shaggy manes. I will breathe air and humus.

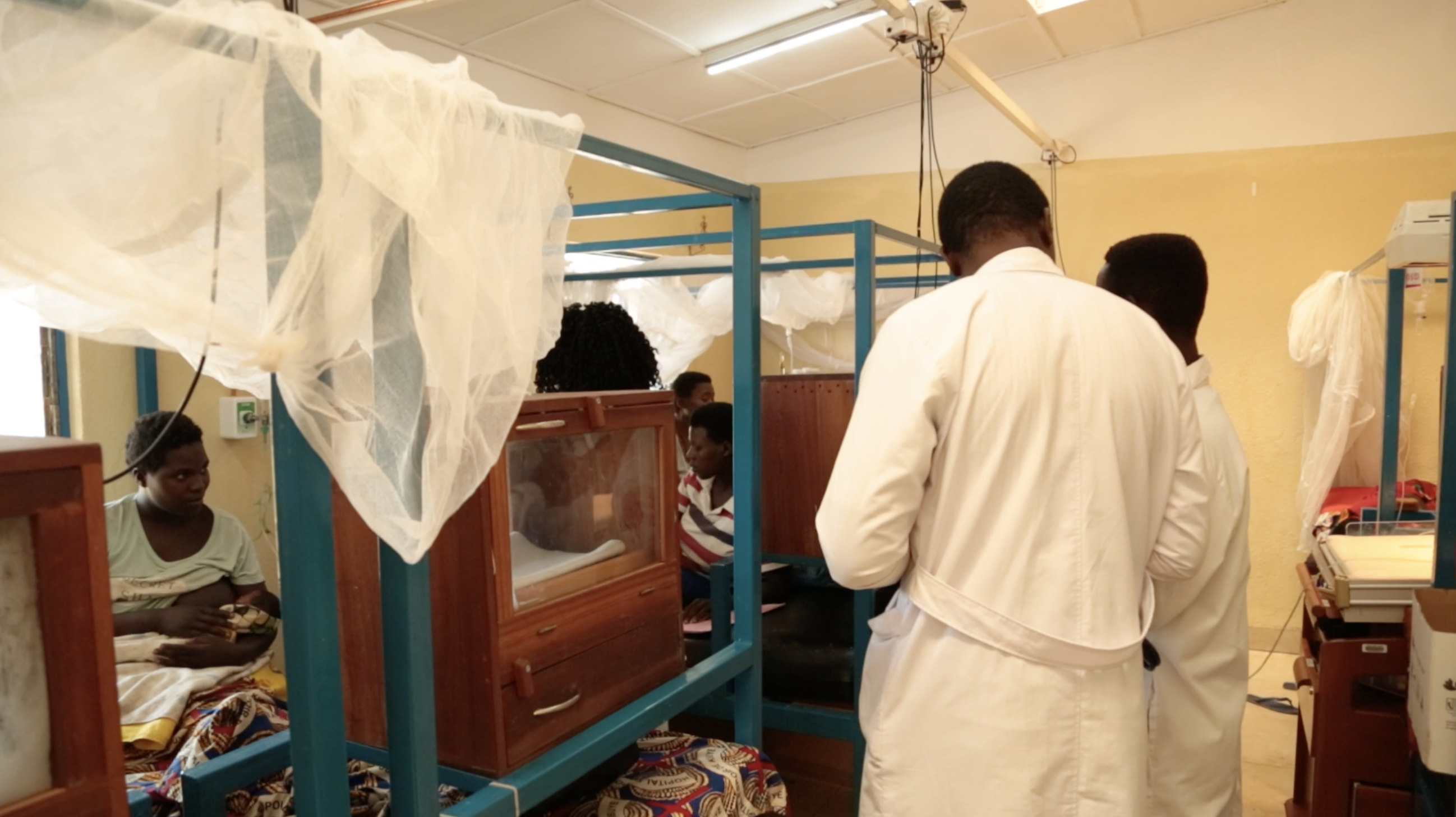

In order to write a poem that is a plough, the poet must first be ploughed under, decompose, and feed a new crop of barley. The reader drinks her ale, breaks her bread with her friends, and is fed.

As she stands up, the earth tilts on its axis.

Here the frailest leaves of me and yet my strongest lasting,

Here I shade and hide my thoughts, I myself do not expose them,

And yet they expose me more than all my other poems.⁷

¹ Heaney, Seamus (1966) "Digging", in Death of a Naturalist.

² Lasky, Dorothea (2010). Poetry Is Not a Project. [online] Ugly Duckling Presse. Available at: https://uglyducklingpresse.org/publications/poetry-is-not-a-project/.

³ Tarkovsky, Andrei and Hunter-Blair, K. (1987) Sculpting in Time. University of Texas Press.

⁴ Le Guin, Ursula K. (2014). Anthropocene: Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. [online] UC Santa Cruz. 8 May. Available at: https://vimeo.com/388580186.

⁵ Baldwin, James (1985). The Creative Process. In: The Price of the Ticket. St. Martin’s Press.

⁶ Alsadir, Nuar (2022) "Invertebrate", in The Yale Review.

⁷ Whitman, Walt (1855) Leaves of Grass.